Growing up, I was told I was half-Italian, half-Irish. My dad’s surname DiMarco is the obvious source of my love of pasta, while my fair skin, light eyes, and love of potatoes came from my red-headed, freckled mother. She would even tell me that my black wavy hair was not from my dad’s side, but from my “black Irish” side. It wasn’t until after they had both died that I did a deeper dive into my heritage to prepare my documentation to claim my Italian citizenship (more on that in another column.)

My dad’s roots checked out. My grandfather was born in a fishing village on the coast of the Adriatic, my grandmother in Lazio not too far from Rome. My dad was born before my grandparent’s naturalized here in the US. I did my mom’s side just for fun and because it was more of a mystery. That’s where the surprises popped up. While her maiden name had Irish roots on her dad’s side (I’m not sharing here for bank password security purposes,) the rest of her heritage was English. I mean, really English. We’re talking founding fathers, colonizers English.

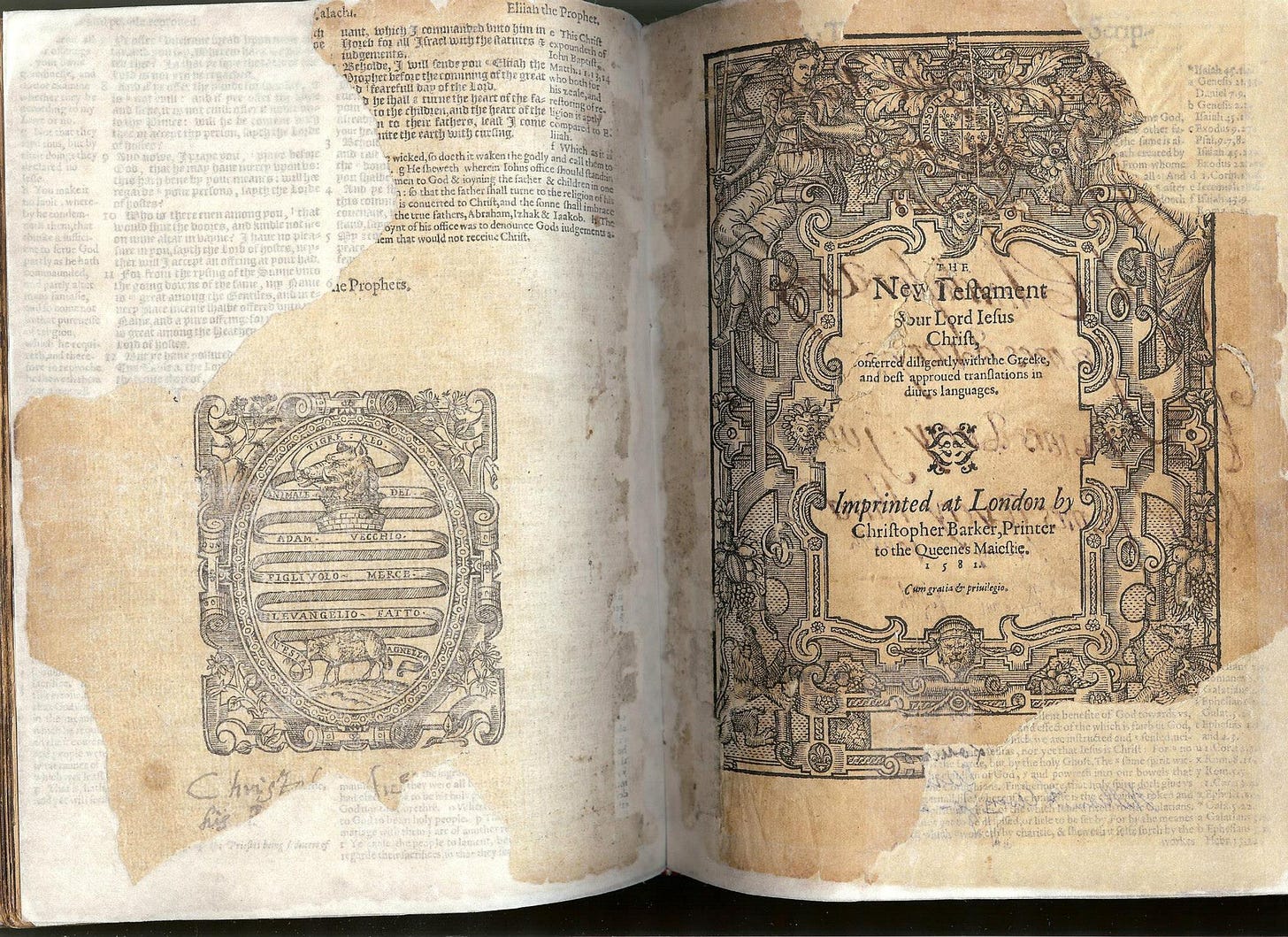

My mom’s mom was an Avery. My 8th Great Grandfather was Captain Christopher Avery, who came to (not-yet) America with his son James in the 1600s. The Avery Family Bible, printed in 1581, came with them and is on display at the Dunham Bible Museum at Houston Baptist University

James Avery, my seventh Great Grandfather, founded the town of Groton, on the outskirts of New London, Connecticut. Shocker of shockers, I come from Puritan stock. Somewhere along the way, an Avery named Lucy married a man named Rockefeller and that whole thing happened.

Yet almost my entire life, my mom only identified as Irish and, by extension, I identified as Italian-Irish descent. Why? As best as I can piece together, my grandmother got divorced from my grandfather when divorce was pretty scandalous and she moved with my mom out West from the Avery enclaves in Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts. My mom didn’t really know her father; the divorce happened when she was too young and, as these sorts of things happen, she romanticized her WWI-serving father and tried to distance herself from her blue blood roots for her red-headed Irish roots.

My mother’s free spirit and borderline rebellion took deeper roots when she met my dad; the son of Italian immigrants when they met in Hollywood at a Christmas Eve party. My Avery grandmother wore black to the wedding to signify her mourning her daughter marrying “interracially.” She really never visited us when I was growing up. There was always a rift between her and my mom.

Why do I share all of this? First, it’s a good story, I think. Second, St. Patrick’s Day is coming up this week and, now that I know more of my heritage, my near yearly tradition of making Irish Stew is now tempered by my newly revealed English roots. But mainly I wanted to illustrate the non-medical term I stumbled across:

Irish Alzheimer’s.

My grandmother eventually did move to my little hometown in Oregon. But it wasn’t to spend more time with her grandkids. No, it was to enter a memory care facility so my mom could watch over her last years of life while my grandmother was battling Alzheimer’s. As I’ve already established, my grandmother wasn’t Irish, she just married an Irishman. But this term and it’s meaning reminded me of my grandmother, mother, and caught me hoping that I won’t suffer from the same fate. Here’s the definition of “Irish Alzheimer’s”:

When you forget everything but the grudges that you hold onto for dear life.

Grudges, personal slights, wounds, and disappointments poison our minds and seemingly reprogram our DNA; we end up disowning family members and whole branches of our family trees. We refuse to forgive and we certainly can’t forget.

I have seen the devastating effects of dementia both in my family and in my spouses. I am praying for a cure or treatment to slow the deterioration of the human mind. But when it comes to the tumorous grudges that spiderweb across our brains and hearts, there is a treatment plan:

Forgiveness.

And before you say, “I can’t forgive!”, I’m not asking you to yet. I’m asking you to remember how you’ve been forgiven; how grudges have been dropped by your Heavenly Father at the mere confession of your sorrow. As you experience the forgiveness that only a perfect and holy God can give, that begins to resequence your DNA to where you can let go of grudges and wanting to get even and, instead, become more like Jesus and entrust yourself to the One who judges justly (1 Peter 2:23.)

St. Patrick’s Day is coming up on March 17th. According to the autobiographical Confessio of Patrick, when he was about sixteen, he was captured by Irish pirates from his home in Britain and taken as a slave to Ireland, looking after animals; he lived there for six years before escaping and returning to his family. After becoming a cleric, he returned to northern and western Ireland.1 Because of the great forgiveness he received from God, he returned to a people he could’ve begrudged and, instead, preached forgiveness of sins through Jesus.

Is there a grudge you can’t let go of? I’d like to pray for you. Is there a relationship where someone won’t let go of a grudge against you? I’d like to pray for you. Comment below or message me on one of my social media accounts and I’ll pray that forgiveness and forgetfulness becomes a part of your DNA and a part of your family tree.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Patrick

This is so good!